African American WWII WAC W. A. A. C. U. S. Army Officer's Womens Female Ladys WW2 B

AN EXTREMELY RARE PHOTOGRAPH OF African American WWII WAC W. Army Officer's Womens Female Ladys WW2 a MEASURING APPROXIMATELY 7 1/2 X 9 1/2 INCHES. I'm going to send a white first lieutenant down here to show you how to run this unit. The general's yell hung in the air, shocking the Soldiers lined up at attention. As chew-outs go, telling a major, a battalion commander, no less, that a lieutenant would be taking over was particularly degrading.

But the general didn't plan to send just any lieutenant. He planned to send a white lieutenant -- the implication, of course, was that the lieutenant would not just be white, but male.

And the general was dressing down one of the highest-ranking African-American women in the Army, the commander of 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. The battalion was the only black Women's Army Corps unit deployed to Europe in World War II. "Over my dead body, sir, " replied Maj. Charity Adams, not sure if she was most insulted by "white, " "first lieutenant" or "white first lieutenant, " she explained in her memoirs, One Woman's Army: A black officer remembers the WAC. She knew she might be court-martialed, so she planned to charge the general, whom she never names, with violating the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Command's rules against explicitly stressing segregation.

Adams was the first African-American woman to be commissioned into the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, in the summer of 1942. The push to include African-Americans in the WAAC had faced challenges, but the efforts of African-American newspapers and activists, including Mary McLeod Bethune, a member of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Black Cabinet, " and her good friend First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, had ultimately prevailed.

A quota was set for 10 percent of the total WAAC, which became the Women's Army Corps (WAC) about a year later. There was space for 40 in the first officer training class, and it was clear they would have to be the best of the best. "I was sure I would never pass, " recalled Capt.

Violet Hill, Company D commander. At that time, I had completed two years of college.Their goal was 40 Negro women who would then form the officer corps that would train the subsequent enlisted women. Their standards, their expectations and their hopes were high.

They preferred women who had not only the education background but also some maturity and work experience, which would be an asset in embarking on an endeavor that was experimental and had a lot riding on it. "There's no doubt that in that first class, both African-American as well as white women, they did really select the best that they could to give the Women's Army Corps the best possible chances, " agreed Dr. Francoise Bonnell, director of the U. Army Women's Museum, noting that the women were all professionals, some with masters' and law degrees.

While the WAAC/WAC was segregated with separate "Negro" companies and barracks -- Adams writes of her shock at being told to step aside with all the other "colored" girls -- it was less so than the rest of the Army, according to Bonnell. The WAC was so small that all of the Soldiers usually trained together, for example, and an attempt to designate colored tables in the cafeteria lasted only a few days when that first group of African-American WACs refused to eat. And in one of her assignments, Adams worked in an all-white office.That's not to say the women didn't encounter blatant racism. Travel, especially throughout the south, could be especially humiliating. "The incident that I'll never forget is when there were four of us having to change trains, " remembered Staff Sgt.

I was informed by a train conductor, we -- and he used the n-word -- could not ride the train. I kept my composure, and I said,'We have to ride it. The military has to know where we are.

In order to ride that train, the officer of the day. And an MP and the conductor -- they found a piece of wrapping paper and some cord and separated us from the white passengers.

Adams tells similar stories, and as she rose through the ranks, her very uniform started to raise questions: "I was waiting with my parents in the small, dirty, and crowded'colored' waiting room in the Atlanta railroad station, " she recalled. There were very many military personnel roaming around the station. So the MPs were constantly moving throughout the crowd.'Some people have -- there was a question -.

I can see your rank. The name of your commanding officer? Adams asked, advising the men to report themselves before she had the chance. They learned a lesson, she wrote, adding that another MP refused to question her when confronted by a suspicious passenger. Those reactions were harbingers of the surprise and hostility she and her executive officer, Capt. Abbie Noel Campbell, encountered when they flew to Europe in January 1945 in advance of their battalion. They were, she wrote, among U. Military personnel who could not believe Negro WAC officers were real. The two women were literally the first black WACs in Europe and, technically, they weren't supposed to be there.Although black Army nurses served in combat zones, when African-Americans had first been allowed to join the WAC, it had been with the proviso that they could never serve overseas. It only happened because of the "needs of the Army, " Bonnell said. That's how we oftentimes see policies and progress.

There was also a push by African-American groups to try to force the War Department to allow and to actually create requisitions for African-American WACs in the European Theater. Eventually, based on this need, a requisition was sent out for 800 women. Many of the women were hand-picked.

They were blazing a trail and they were expected to excel. They had to be, as Adams told her troops, the best WAC unit ever sent into a foreign theater. The eyes of the public would be upon us, waiting for one slip in our good conduct or performance. "One day I came home from work.'Your name's on the board,'" remembered Staff Sgt.There was a list of girls selected to go overseas. I went in to my commanding officer Capt. And she said,'I selected the girls that I would like to go overseas with me.. It was an honor for her to think that much of me.

After long, fraught journeys across the Atlantic that involved shadowing by German U-boats and a V-1 "buzz" bomb that landed just as some of them disembarked in Scotland, the Soldiers of the 6888th arrived in Birmingham, England, in February 1945. They were stationed at an old school and it must have been a dismal prospect. Mattresses were made from straw; showers were in the courtyard and heat was almost nonexistent. This was actually the reason the general accused Adams of incompetence.

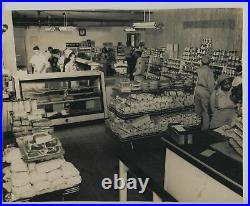

He expected to inspect the whole battalion and was livid when only a third of the Soldiers were available. He later apologized and told her he respected her for standing up to him. "They supplied us with files, the names of men who were enlisted in the Army in the European Theater, " remembered Pfc. You know what was so exciting about that?There was part of the history of these men on the files. You knew that he had not gotten any news from his family or friends. And you were determined to try to find him.

It required immense attention to detail. And then there were the name duplications."At one point, " Adams wrote, we had more than 7,500 Robert Smiths. There were, of course, tens of thousands of Roberts with other last names. Moreover, there were variations of first names, nicknames, that are used in the United States: Bob, Rob, Bobby, Robby, Bert, and so forth, just for Robert.

The military would photograph certain letters and send them overseas on microfilm. It saved space and weight but was time-consuming. Then they were off to Rouen, France, to tackle another backlog, and then Paris.

Tragedy struck in France, where three of the WACs died in a jeep accident while on furlough. They were buried in Normandy. Furloughs were common, however, and the women found time to relax and travel despite their heavy workloads. The 6888th veterans also all spoke of how friendly the people of were, particularly the people of Birmingham, welcoming the WACs into their homes and treating them with a respect many had never experienced at home -- or with their own countrymen in Europe. Although black and white WACs had initially used the same Red Cross hotels and recreation facilities without incident, one day Red Cross officials proudly announced that they had procured a separate hotel for the 6888th in London, suggesting the WACs would prefer it that way.As far as she knew, no one ever did. It was, she wrote, an opportunity to stand together for a common cause. Adams, who would soon be promoted to lieutenant colonel, was the highest-ranking woman aboard, leaving her in command of not only her unit, but also a white Army Nurse Corps detachment. They refused to accept Adams' authority.

Tired and fed up, Adams struggled to keep her temper under control. If you cannot go home under my command, I suggest you pack your belongings. You have 20 minutes to get off. I don't care whether you go home or not, but if you go, you go under my command.He corrected her: The women would have only 17 minutes to disembark. Asked Bonnell, noting that military courtesies usually won out. She explained that after the war, many of the WACs used their GI Bill benefits for college and even graduate school, becoming educators, lawyers, community leaders and social activists. Adams herself became a college dean.

"The experience of African-American women at this particular time lays the groundwork for change, not only for their race, but also for women in general, " she continued. We see progress in terms of the changes in military policy and opportunities taking place for women in part because of the challenges women experienced in World War II, none more so than African-American women.

And the responsibility to deliver all of it fell on the shoulders of 855 African-American women. Because of a shortage of resources and manpower, letters and packages had been accumulating in warehouses for months. But these women did far more than distribute letters and packages. As the largest contingent of black women to ever serve overseas, they dispelled stereotypes and represented a change in racial and gender roles in the military.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. Inspect the first contingent of Negro members of the Women's Army Corps assigned to overseas service. When the United States entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, there was no escaping the fact that women would be essential to the war effort. With American men serving abroad, there were countless communications, technical, medical and administrative roles that needed to be filled.The Women's Army Corps-originally created as a volunteer division in 1942 until it was fully incorporated into the army by law in 1943-became the solution. READ MORE: Pearl Harbor Attack: Photos and Facts. WACs attracted women from all socio-economic backgrounds, including low-skilled workers and educated professionals. As documented in the military's official history of the 6888th, black women became WACs from the beginning. Civil rights activist and educator Mary McLeod Bethune, a personal friend of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and a special assistant to the war secretary, handpicked many of them.

"Bethune was lobbying and politicking for black participation in the war and for black female participation, " says Gregory S. Cooke, an historian at Drexel University, whose documentary, Invisible Warriors: African American Women in World War II, highlights African American Rosie the Riveters. Black women were encouraged to become WACs because they were told they wouldn't face discrimination. In other divisions, such as the Navy, black women were excluded almost entirely, and the Army Nurse Corps only allowed 500 black nurses to serve despite thousands who applied.READ MORE: When Black Nurses Were Relegated to Care for German POWs. Becoming a WAC also gave African-American women, often denied employment in civilian jobs, a chance for economic stability. Others hoped for better race relations, as described in scholar Brenda L. Moore's book, To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race: The Story of the Only African American WACs Stationed Overseas during World War II.

One WAC Elaine Bennett said she joined because I wanted to prove to myself, and maybe to the world, that we [African Americans] would give what we had back to the United States as a confirmation that we were full-fledged citizens. But discrimination still infiltrated the Women's Army Corps.

Despite advertisements that ran in black newspapers, there were African American women who were denied WAC applications at local recruitment centers. And for the 6,500 black women who would become WACs, their experiences were entirely segregated, including their platoons, living quarters, mess halls and recreational facilities. A quota system was also enforced within the Women's Army Corps. The number of black WACS could never exceed 10 percent, which matched the proportion of blacks in the national population.

"Given the racial, social and political climate, people were not clamoring to have blacks under their command, " says Cooke. The general perception among commanders was to command a black troop was a form of punishment. The jobs for WACs were numerous, including switchboard operator, mechanic, chauffeur, cook, typist and clerk. Whatever noncombat position needed filling, there was a WAC to do it. But the stresses of war changed the trajectory of black women in November 1944, when the war department lifted a ban on black WACs serving overseas. Led by African American Commander Charity Adams Earley, the 6888 Central Postal Directory was formed-an all-black, female group of 824 enlisted women, and 31 officers. Within the selected battalion, most had finished high school, several had some years of college and a few had completed a degree. READ MORE: How Women Fought Their Way Into the U. Black soldier visit an open house hosted by the 6888th Central Postal Directory shortly after their arrival in Europe i n 1945. After their training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, which entailed crawling under logs with gas masks and jumping over trenches, the 6888th sailed across the Atlantic, arriving in Birmingham, England, in February 1945. Divided into three separate, 8-hour shifts, the women worked around the clock seven days a week. They kept track of 7 million identification cards with serial numbers to distinguish between soldiers with the same names.To their relief, the 6888 had a congenial relationship with the Birmingham community. It was common for residents to invite the women over for tea, a sharp contrast to the segregated American Red Cross clubs the 6888th couldn't enter. READ MORE: Did World War II Launch the Civil Rights Movement?

After finishing their task in Birmingham, in June 1945, the 6888 transferred to Rouen, France, where they carried on, with admiration from the French, and cleared the backlog. While the work was taxing, as an all-black, female unit overseas, they understood the significance of their presence. "They knew what they did would reflect on all other black people, " says Cooke. The Tuskegee Airmen, the 6888 represented all black people. Had they failed, all black people would fail.

And that was part of the thinking going into the war. The black battalions had the burden that their role in the war was about something much bigger than themselves. In January 1941, the Army opened its nurse corps to blacks but established a ceiling of 56. On June 25, 1941, President Roosevelt's Executive Order 8802 created the Fair Employment Practices Commission which led the way in eradicating racial discrimination in the defense program. In June 1943, Frances Payne Bolton, Congresswoman from Ohio, introduced an amendment to the Nurse Training Bill to bar racial bias.

Soon 2,000 blacks were enrolled in the Cadet Nurse Corps. The quota for black Army Nurses was eliminated in July 1944. More than 500 black Army nurses served stateside and overseas during the war.

The Navy dropped its color ban on January 25, 1945, and on March 9, Phyllis Daley became the first black commissioned Navy nurse. Black women also enlisted in the WAAC (Women's Army Auxiliary Corps) which soon converted to the WAC (Women's Army Corps), the Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), and the Coast Guard SPARS. From its beginning in 1942, black women were part of the WAAC. When the first WAACs arrived at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, there were 400 white and 40 black women. Dubbed "ten-percenters, " recruitment of black women was limited to ten percent of the WAAC population-matching the black proportion of the national population. Enlisted women served in segregated units, participated in segregated training, lived in separate quarters, ate at separate tables in mess halls, and used segregated recreation facilities. Officers received their officer candidate training in integrated units, but lived under segregated conditions. Specialist and technical training schools were integrated in 1943.During the war, 6,520 black women served in the WAAC/WAC. Black women were barred from the WAVES until October 19, 1944. The efforts of Director Mildred McAfee and Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune helped Secretary of the Navy Forrestal push through their admittance.

The first two black WAVES officers, Harriet Ida Pikens and Frances Wills, were sworn in December 22, 1944. Of the 80,000 WAVES in the war, a total of 72 black women served, normally under integrated conditions. The Coast Guard opened the SPARS (from the Coast Guard motto Semper Paratus, "AlwaysReady") to black members on October 20, 1944, but only a few actually enlisted. The Path to Full Integration. Following World War II, racial and gender discrimination, as well as segregation persisted in the military.

Entry quotas and segregation in the WAC deterred many from re-entry between 1946 and 1947. By June 1948, only four black officers and 121 enlisted women remained in the WAC. President Truman eliminated the issues of segregation, quotas and discrimination in the armed forces by signing Executive Order 9981 on July 26, 1948. WACs began integrated training and living in April 1950. Meanwhile, on January 6, 1948, Ensign Edith De Voe was sworn into the Regular Navy Nurse Corps and in March, First Lieutenant Nancy C.

Leftenant entered the Regular Army Nurse Corps, becoming the corps' first black members. Affirmative action and changing racial policies opened new doors for black women. During the Korean and Vietnam Wars, black women took their places in the war zone. As we make our way through Women's History Month, we are reminded of the incredible accomplishments of women throughout history.

This year, we would like to focus on women who served, particularly African American women in World War II. For some great background information, be sure to visit our previous blog - Their War Too: Women in the Military During WWII.

America's entrance into World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 was met with pride and patriotism across the country. American citizens surged to enlist in all branches of the US Military and women wanted to serve their country too.

Their challenge actually began earlier that year, in May of 1941. Dovey Johnson Roundtree, who would go on to become one of the first 39 black women Officers, worked with Eleanor Roosevelt, Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers, and Mary McLeod Bethune to draft the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) resolution that was presented to Congress. With support from the General of the Army George Marshall, the bill passed both House of Representatives and then the Senate in May of 1942. With the WAAC in place, the War Department announced that it would follow Army policy, and admit black women with a 10-percent quota. Before recruitment and training even began, African American women faced the hurdle of discrimination.

Applications for the first contingent of officer candidates was available at the United States Post Office, and many African American women that applied were turned away on the spot, simply because of their race. There is no telling how many women this discouraged, as discrimination became a recurring problem for WAC recruitment. The first class of officer candidates consisted of 440 women - 39 of whom were black. Not only did black women face the hardship of discrimination outside of the military, but faced segregation within.Black WAACs were in a separate company than white trainees, had separate lodging, dining tables, and even recreation areas. At the end of training, there were only 36 black women of the 436 WAACs to graduate with the rank of third officer.

The Army wasn't the only branch where women wanted to serve, and other women's units were established. Women who wanted to help the Navy joined the WAVES, the Coast Guard had the SPAR, the Air Force had WASP, and the Marines Corps had the WR. The WAAC however was the only branch to allow black women from its inception.Despite this fact, recruitment of black women proved difficult. Segregation meant many black women didn't want to join, and black WAACs still faced discrimination.

The Black Press Pool helped monitor and speak out against discrimination in the military, including within the WAACs. Reports came out that black WAACs with college degrees were being assigned to clean floors, and given laundry duty. The press demanded a black woman to be assigned to the WAAC director's office to monitor and address discrimination complaints. In July of 1943, it was announced that the women of WAAC would be classified under the same ranks as soldiers, a big victory for women's equality. The unit name changed to the Women's Army Corps (WAC). African American WACs didn't receive the same specialized training that white WACs had, and most were trained in motor equipment, cooking, or administrative work. One of the biggest complaints amongst African American WACs was that there were no black WACs overseas. Unfortunately, the WAC had to abide by all Army regulations, and overseas commanders had the right to designate race or color of units being sent, and no black WACs were requested.Eleanor Roosevelt intervened on their behalf however, and the War Department directed commanders to accept African American WACs. The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion was a unit of more than 800 black WACs, and was the only black WAC unit to serve overseas. When the WACs arrived, they found the building stacked to the ceiling with mailbags, and another room filled with packages of spoiled food and gifts, along with rodents. Charity Adams, one of only two black WACs promoted to the rank of major during World War II, was the commander of this unit.

She was proud of the work her unit did, performing their tasks in record time. Once finished in Birmingham, the unit went on to Rouen, France, and ultimately Paris. While the WAC was by far where most black women served, it wasn't the only place.

World War II saw about 500 black nurses in the army, the WAVES eventually saw almost 100 black women, and the Coast Guard's SPAR had 5 black women who served. The Army Nurse Corps initially followed the War Department guidelines of the quota system, which severely limited the number of black women admitted. It wasn't until a severe nursing shortage that the quota was lifted. Despite the importance that African American women played in the war effort, little is seen of them in war production materials. They are conspicuous only in their absence from recruitment films, as the topic of race was generally avoided.We were fortunate enough to find some footage from Record Group 111 (Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer) Series ADC (Moving Images Relating to Military Activities) that featured black WACs, including Major Charity Adams. These women not only faced the scrutiny and prejudice of friends and family for wanting to join the military, they also had to deal with discrimination and segregation.

It was challenging and often thankless, but they saw the importance of their work, and persevered. These women were truly trailblazers, opening up opportunities for women of color in an area previously dominated by white men, and for that they are honored. The two clips from the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer highlighted in this post can be viewed in their entirety below. Bolzenius's Glory in Their Spirit: How Four Black Women Took On the Army During World War II details a critical March 1945 incident: the strike and subsequent trial of African American members of the Women's Army Corps (WAC) at Ft. Bolzenius situates the strike within the context of civil rights activism and Black women's labor history.Glory in Their Spirit makes an important contribution to African American history and the history of World War II. Bolzenius explains that many Black women who joined the WAC for career opportunities were instead assigned to the least skilled work, often involving cleaning or other menial labor. Devens, Black WACs who had been promised training as medical technicians were assigned to be hospital orderlies, a far less technical and prestigious job, and one to which Black WACs at Ft. Devens were disproportionately assigned, relative to white WACs. This disparate treatment in labor assignments and working conditions, the Army's policy of racial segregation, and frustration with officers in the chain of command created substantial morale problems in the detachment, culminating in fifty-four Black WACs refusing to go to work.

Upon threat of court-martial most of the women went back to work as ordered, but four continued to strike and were charged with disobeying an order of a superior officer. Drawing from multiple military investigations of the event, the court-martial transcript, and a wide variety of other archival sources, Bolzenius writes a lively narrative that moves from the origins of the strike and the strike itself to the court-martial that followed and the trial's aftermath. At the same time, she pays attention to individual histories and motivations, showing why these four women-Mary Green, Anna Morrison, Johnnie Murphy and Alice Young-held out all the way to trial. Although her focus is on the defendants, we also learn about the Black and white officers involved, demonstrating how failures of leadership at multiple levels of the military hierarchy contributed to the circumstances that led to the strike. Bolzenius argues that the strike was a protest of racial and gender discrimination in both the Army as a whole and specifically at Ft.The strikers viewed themselves as defending African American people and specifically African Americans WACs. The Army, on the other hand, suggested that the WACs were merely complaining because they did not like their work.

However, the women were upset not by the nature of their work, but by the fact that they were not being given the same training opportunities and range of possible job assignments open to white WACs. Bolzenius shows how the focus on military protocol, although ostensibly impartial, actually contributed to circumstances that made defense of the court-martial charges very difficult. For example, all members of the court-martial hearing the case outranked the defendants, which is still a requirement in contemporary courts-martial. Additionally, although the panel's inclusion of two Black men and three white women made for a more diverse group than would have been achieved on many civilian juries, no members were African American women. The fact that the military did not consider racial discrimination a valid defense at court-martial also constrained the defense strategy.

Bolzenius' discussion of this strategy in Chapter Four is particularly fascinating. Because racial discrimination was not considered a valid defense, NAACP lawyer Julian Rainey argued that the defendants were so focused on their own perceptions of discrimination that they became temporarily insane. Rainey presented evidence that there was, in fact, racial discrimination at Ft. Devens, but because of the constraints on acceptable defenses he could not explicitly make that accusation. Bolzenius argues that Rainey described the defendants as confused and mentally unstable in his attempts to explain their actions, relying on "a patriarchal perspective of women's weaknesses, " even when his clients themselves told a different story (99).

Instead, the strategy of focusing on the women's perception of discrimination implied the possibility that the perception was imagined and drew on gender stereotypes of women as hysterical. Bolzenius also shows how the women's own testimony describing their decisions to strike differed from their lawyer's portrayal. The defense was unsuccessful, as all four women were convicted and were each initially sentenced to dishonorable discharge, loss of pay, and one year of imprisonment with hard labor. Bolzenius demonstrates that the intersection of race, gender, and rank influenced not only the conditions to which the women were subject within the Army, but also the unusual media interest the strike and trial captured. Although courts-martial were much more common during World War II than they are today, military trials of female personnel were rare, especially when the case involved African American WACs and allegations of racial discrimination. The nature of the case inspired considerable public interest, including extensive press coverage, especially in Black newspapers. The War Department was inundated with correspondence from citizens, civil rights leaders, and even a Congressional inquiry into four attempted suicides that occurred in the detachment in February and March 1945, around the time of the strike and the trial. Ultimately, in Bolzenius' view, it was also the military emphasis on protocol that resulted in the reversal of the women's convictions.The War Department found a way out from the continued media attention from the case and its upcoming appeal, for which Thurgood Marshall had agreed to represent the women, by deciding that the court-martial had been convened by the wrong officer. The subsequent War Department investigation of the strike attributed the event to the poor leadership of the officer serving as the hospital administrator, rather than any discriminatory military policies. Although Bolzenius convincingly places the strike within a broader history of Black women's labor activism, a more detailed discussion of previous strikes by African American service members, especially the Port Chicago mutiny and its subsequent courts-martial, might have enriched the book. Some of these incidents are mentioned, but the influence of other military labor protests on the Ft.

Devens strike and on the War Department's response could have been considered more extensively. Nonetheless, Glory in Their Spirit is a compelling, deeply researched book that will appeal to both academic and non-academic readers interested in a variety of subjects, including, but not limited to, Black women's history, labor history, and military history.

In late 1944, four African-American women-Mary Green, Anna Morrison, Johnnie Murphy and Alice Young-enlisted in the Women's Army Corps, or WAC, the newly established military branch for women. All were eager to help the nation's fight for democracy by learning skills the army desperately needed, and all believed that later these skills would improve their employment prospects for the future. Instead, within a year after reporting for duty, the young women stood in the dock at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, charged with disobeying orders. The Fort Devens strike and court-martial was one the most publicized courts-martial of World War II; largely forgotten today, it was a curiosity that fascinated Americans in its time. Trials of black servicemen were routine, yet those involving women in uniform-an impossibility until the creation of the WAC just three years before-were rare.

The case served as a proxy for many of the war's controversies, including debates about women's suitability for military service and about racial segregation in the armed forces. It also brought into question Americans' domestic commitment to the values of democracy for which they were fighting. The records from the Fort Devens WAC case provide insight into the systemic exclusion of black women. More than 6,500 black women volunteered for the WAC during World War II, an era when "Negro" signified black men and "women" signified white females. Each of their enlistments posed a bold challenge to other Americans, to recognize these soldiers as black and female patriots. The story of the Fort Devens court-martial details how onerous, unforgiving, and lonely that challenge was. Green, Morrison, Murphy, and Young were all in their early 20s when they enlisted in the WAC, a new corps established to help the army meet personnel needs for a two-front global war.Wacs (as individual female service members were known) were intended to replace male soldiers in important support positions, freeing the men for field and combat service. The WAC cautiously avoided upsetting conventional gender paradigms. Aggressively advertising in newspapers and on the radio, it recruited women for suitably feminine jobs such as clerical workers and medical technicians, though it also prepared some to become drivers and aircraft mechanics, or to fill other non-combat jobs that had formerly been restricted to men. Crucially, the WAC promised to train women for skilled assignments. This appealed to Green and Morrison, who were seeking an escape from maid work; to Young, who had left nursing college but still harbored nursing ambitions; and to Murphy, who had clerical training, though no job.

In October, the four women arrived at Fort Devens, which had been chosen to house a black WAC detachment of 100 people. They had orders to report to the post hospital. As Young recalled, they were excited because the whole company was under the impression that we had come here to go to medical technicians school.

Instead, officers assigned them to clean the hospital and wait on staff and patients. The women called it maid work. As one of the Wacs told her black officer, we get tired of just washing and cleaning, and every time what they see something they tell us to wash this and wash that.

It looks like every time they want some of the bad work done they say,'go get one them Wacs. Tell her to do so and so. Aghast by their confinement to peripheral and menial tasks-especially while all but a handful of white Wacs worked in skilled assignments such as teletypist, X-ray technician, chaplain assistant, or driver-the black Wacs complained to their superiors, who ignored their concerns. During World War II, the U.

Army often assigned black servicewomen to menial jobs. Courtesy of theNational Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons. Everything changed on March 9, 1945, when nearly all of the black orderlies at the base refused to report to their duty stations. The strike, a mutiny in military terms, lasted into the next day, ending after an extraordinary intervention from the chief officer of the First Service Command, General Sherman Miles. Days later, Murphy, who had been on leave the day of the strike, joined them, proclaiming, I would take death before I would go back to work. The women's trial commenced nine days after the March 10 arrests. Throughout the proceedings, the army prosecutor focused on the defendants' failure to obey orders. The Wacs, in turn, accused their officers of discrimination. Their officers refuted the charge, insisting that the army did not discriminate against black Wacs-at Fort Devens or elsewhere. Indeed, bowing to pressure from an emboldened civil rights movement, the service had announced in 1940 the equal treatment of troops regardless of race and, in 1942, accepted black female recruits (initially, the only service to do so) under the same policy.The problem was that under the military's newly announced policies, "not discriminating" still resulted in a segregated army where officers had power to utilize troops "where they best fit"-and military policies assured an awkward fit for black Wacs. The War Department maintained separate directives for black soldiers (prioritizing segregation) and for female soldiers (prioritizing their status as assistants), and applied both sets of regulations to black Wacs. White Wacs could attend a wide range of schools that remained off-limits to black Wacs, even when they were qualified. The complexities of organizing separate barracks, courses, and facilities, per army segregation policies, made offering black Wacs better training too expensive and cumbersome. Alice Young had attended nursing college and Johnnie Murphy a clerical course, but that didn't matter-both still were stuck working as orderlies.

When a frustrated Young requested admittance to Fort Devens' driving school, which conducted sessions for black soldiers and for white Wacs, she was turned down because the post did not have classes for black Wacs. When investigators looked into the issue following the court-martial, they concluded that the motor pool did not discriminate. Offering driving courses for black men and for (white) women was deemed sufficient.WAC director Oveta Culp Hobby hewed to established policies that marginalized the black Wacs even further. She ordered that every black unit have a black Wac commander, a practice that created self-contained units that could be, and often were, isolated. Concerned about the reputed sexual promiscuity of African-American women, Hobby refused to send black Wacs overseas until pressured to do so in the last year of the war. She curtailed the recruitment of black women in hopes of lessening their numbers and, conversely, she assumed, encouraging white enlistments.

The army demonstrated concern for white Wacs' morale but ignored black Wacs' woes. Before black Wacs arrived at Fort Devens, some white Wacs had worked as orderlies. When they complained, officers organized medical classes for them.

When their black replacements pushed back, officers disregarded their grievances. "As far as I'm concerned, " white army nurse Lieutenant Simone Parent told investigators, "I think they just wanted something to complain about, " later remarking, "you can't trust them, " but assuring her interviewers that it wasn't a racial thing. White Wacs, perched in the better jobs, were perceived as good soldiers who followed orders and got along with others.

Black Wacs, consigned to scrubbing floors and pushing heavy food carts, were viewed as constant complainers who performed poorly and perfunctorily blamed racism. Their enlistments posed a bold challenge to other Americans, to recognize these soldiers as black and female patriots.Black men in the service also suffered under segregation, yet as men were accepted as soldiers where black Wacs were not. "These are women and Wacs really aren't soldiers, " The Washington Post noted, of the Fort Devens strikers. One campaign to support the defendants-launched by black legionnaires-appealed to the army's understanding that Wacs were naturally more frail, impulsive and sensitive than men. Even the Wacs' NAACP lawyer, Julian Rainey, rested his defense on this premise. A World War I veteran who well knew racial discrimination in the military, he attempted to free his clients by questioning their intelligence and repeatedly characterizing them as confused by something they couldn't understand.

Black men routinely praised the courage and determination of black servicemen who breached military protocol in defense of African Americans' rights, but did not necessarily perceive black women as equally capable or self-sacrificing. Green, Morrison, Murphy, and Young "didn't know what they were doing, " Rainey argued at trial.

But the black Wacs did know what they were doing. They had enlisted in the WAC based on army policies that guaranteed fair treatment, and they broke protocol only after realizing that those policies did not uniformly apply to them. You see, I thought I was a citizen. Private Mary Johnson felt the same. "We might have gone about it the wrong way, " she admitted, but the thing we were fighting for was justice and rights. We want to live like other people. Many Americans, riveted to the story as told by the black and mainstream presses, came around to the strikers' side. Ordinary citizens joined civil rights leaders in protests, including besieging the offices of President Franklin D.Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry Stimson with letters demanding an investigation and for the just treatment of the Wacs on trial. Caught off guard by the public's fascination with the case and unsettled by the questions that these women's experiences provoked, the War Department quickly dismissed the charges and released the women back to their unit, following up with an investigation which noted problems with the treatment of black Wacs but changed little. Green, Morrison, Murphy, and Young and the other black Wacs at Fort Devens worked as orderlies throughout the remainder of their time in the WAC.

Within two months of the strike, the newspapers had stopped writing about it. They had other news to report: stories about black servicemen who bravely battled segregation and white Wacs who carved new paths for women that today are familiar, and inspiring, World War II narratives.For a brief moment during the spring of 1945, however, Anna Morrison, Mary Green, Alice Young, and Johnnie Murphy put black women in uniform front and center for Americans- reminding them, uncomfortably, that they lived in a country where some patriots still didn't fit. The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942 by Public Law 554, [1] and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United States as the WAC on 1 July 1943. Its first director was Oveta Culp Hobby, a prominent woman in Texas society. [2][3] The WAC was disbanded in 1978, and all units were integrated with male units.

Pallas Athene, official insignia of the U. Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association. The WAAC's organization was designed by numerous Army bureaus coordinated by Lt. Mudgett, the first WAAC Pre-Planner; however, nearly all of his plans were discarded or greatly modified before going into operation because he expected a corps of only 11,000 women.

[4] Without the support of the War Department, Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill on 28 May 1941, providing for a women's army auxiliary corps. The bill was held up for months by the Bureau of the Budget but was resurrected after the United States entered the war. The senate approved the bill on 14 May 1941 and became law on 15 May 1942. [5] When President Franklin D.

Roosevelt signed the bill the next day, he set a recruitment goal of 25,000 women for the first year. That goal was unexpectedly exceeded, so Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson decided to increase the limit by authorizing the enlistment of 150,000 volunteers. The WAAC was modeled after comparable British units, especially the ATS, which caught the attention of Chief of Staff George C.[7] Members of the WAC became the first women other than nurses to serve within the United States Army. [8] In 1942, the first contingent of 800 members of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps began basic training at Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School, Iowa. The women were fitted for uniforms, interviewed, assigned to companies and barracks and inoculated against disease during the first day. The WAAC were first trained in three major specialties.

The brightest and nimblest were trained as switchboard operators. Next came the mechanics, who had to have a high degree of mechanical aptitude and problem solving ability. The bakers were usually the lowest scoring recruits and were stereotyped as being the least intelligent and able by their fellow WAACs.[citation needed] This was later expanded to dozens of specialties like Postal Clerk, Driver, Stenographer, and Clerk-Typist. WAC armorers maintained and repaired small arms and heavy weapons that they were not allowed to use. A physical training manual titled "You Must Be Fit" was published by the War Department in July 1943, aimed at bringing the women recruits to top physical standards. The manual begins by naming the responsibility of the women: Your Job: To Replace Men.

Be Ready To Take Over. [10] It cited the commitment of women to the war effort in England, Russia, Germany and Japan, and emphasized that the WAC recruits must be physically able to take on any job assigned to them.The fitness manual was state-of-the-art for its day, with sections on warming up, and progressive body-weight strength-building exercises for the arms, legs, stomach, and neck and back. It included a section on designing a personal fitness routine after basic training, and concluded with "The Army Way to Health and Added Attractiveness" with advice on skin care, make-up, and hair styles. Inept publicity and the poor appearance of the WAAC/WAC uniform, especially in comparison to that of the other services, handicapped recruiting efforts. [citation needed] A resistance by senior Army commanders was overcome by the efficient service of WAACs in the field, but the attitude of men in the rank and file remained generally negative and hopes that up to a million men could be replaced by women never materialized. The United States Army Air Forces became an early and staunch supporter of regular military status for women in the army.

About 150,000[11] American women eventually served in the WAAC and WAC during World War II. They were the first women other than nurses to serve with the Army. [12] While conservative opinion in the leadership of the Army and public opinion generally was initially opposed to women serving in uniform, [citation needed] the shortage of men necessitated a new policy. WACs working in the communications section of the operations room at an air force station.While most women served stateside, some went to various places around the world, including Europe, North Africa, and New Guinea. For example, WACs landed on Normandy Beach just a few weeks after the initial invasion. In 1943 the recruiting momentum stopped and went into reverse as a massive slander campaign on the home front challenged the WACs as sexually immoral. [14] Many soldiers ferociously opposed allowing women in uniform, warning their sisters and friends they would be seen as lesbians or prostitutes.

[15] Other sources were from other women - servicemen's and officer's wives' idle gossip, local women who disliked the newcomers taking over "their town", female civilian employees resenting the competition (for both jobs and men), charity and volunteer organizations who resented the extra attention the WAACs received, and complaints and slander spread by disgruntled or discharged WAACs. [16] All investigations showed the rumors were false. Although many sources spawned and fed bad jokes and ugly rumors about military women, [19] contemporaneous[20][21] and historical[22][23] accounts have focused on the work of syndicated columnist John O'Donnell. According to an Army history, even with its hasty retraction, [24] O'Donnell's June 8, 1943 "Capitol Stuff" column did incalculable damage. "[25] That column began, "Contraceptives and prophylactic equipment will be furnished to members of the WAACS, according to a super secret agreement reached by the high ranking officers of the War Department and the WAAC chieftain, Mrs. "[26] This followed O'Donnell's June 7 column discussing efforts of women journalists and congresswomen to dispel "the gaudy stories of the gay and careless way in which the young ladies in uniform. The allegations were refuted, [21][28][29] but the fat was in the fire. The morals of the WAACs became a topic of general discussion.. [30] Denials of O'Donnell's fabrications[31] and others like them were ineffectual. [32] According to Mattie Treadwell's Army history, as long as three years after O'Donnell's column, religious publications were still to be found reprinting the story, and actually attributing the columnist's lines to Director Hobby. Director Hobby's picture was labeled'Astounding Degeneracy'.. Black women served in the Army's WAAC and WAC, but very few served in the Navy. [34] African American women serving in the WAC experienced segregation in much the same fashion as in U. Some billets accepted WACs of any race, while others did not.[35] Black women were taught the same specialties as white women, and the races were not segregated at specialty training schools. The US Army goal was to have 10 percent of the force be African-American, to reflect the larger U. Population, but a shortage of recruits brought only 5.1 percent black women to the WAC. WACs operate teletype machines during World War II.

General Douglas MacArthur called the WACs "my best soldiers", adding that they worked harder, complained less, and were better disciplined than men. [37] Many generals wanted more of them and proposed to draft women but it was realized that this "would provoke considerable public outcry and Congressional opposition", and so the War Department declined to take such a drastic step. [38] Those 150,000 women who did serve released the equivalent of 7 divisions of men for combat. Eisenhower said that "their contributions in efficiency, skill, spirit, and determination are immeasurable". [39] Nevertheless, the slander campaign hurt the reputation of the WAC and WAVES; many women did not want it known they were veterans.During the same time period, other branches of the U. Military had similar women's units, including the Navy WAVES, the SPARS of the Coast Guard, United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve, and the (civil) Women Airforce Service Pilots.

The British Armed Forces also had similar units, including the Women's Royal Naval Service ("Wrens"), the Auxiliary Territorial Service. And the Women's Auxiliary Air Force.

According to historian D'Ann Campbell, American society was not ready for women in military roles. The WAC and WAVES had been given an impossible mission: they not only had to raise a force immediately and voluntarily from a group that had no military traditions, but also had overcome intense hostility from their male comrades. Although the military high command strongly endorsed their work, there were no centers of influence in the civilian world, either male or female, that were committed to the success of the women's services, and no civilian institutions that provided preliminary training for recruits or suitable positions for veterans. Wacs, Waves, Spars and women Marines were war orphans whom no one loved.This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Women's Army Corps" - news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). Wacs were assigned to the Corps of Engineers since early 1943.

Four-hundred twenty-two personnel were employed on the project. Groves, commander of the project, wrote: Little is known of the significance of the contribution to the Manhattan Project by hundreds of members of the Women's Army Corps... Since you received no headline acclaim, no one outside the project will ever know how much depended upon you.

The women interviewed for positions on the project were told they would do a hard job, would never be allowed to go overseas or attend officer candidate school, would never receive publicity, and would live at isolated stations with few recreational facilities. A surprising number of highly qualified women responded. WAC units involved in this effort were awarded the Meritorious Unit Service Award; twenty women received the Army Commendation Ribbon; and one received the Legion of Merit. The WAC as a branch was disbanded in 1978 and all female units were integrated with male units. Women serving as WACs at that time converted in branch to whichever Military Occupational Specialty they worked in. Since then, women in the US Army have served in the same units as men, though they have only been allowed in or near combat situations since 1994 when Defense Secretary Les Aspin ordered the removal of "substantial risk of capture" from the list of grounds for excluding women from certain military units.In 2015 Jeanne Pace, at the time the longest-tenured female warrant officer and the last former member of the WAC on active duty, retired. [43][44][45] She had joined the WAC in 1972.

WAC Signal Corps field telephone operators, 1944. Originally there were only four enlisted (or "enrolled") WAAC ranks (auxiliary, junior leader, leader, and senior leader) and three WAC officer ranks (first, second and third officer). The Director was initially considered as equivalent to a major, then later made the equivalent of a colonel. The enlisted ranks expanded as the organization grew in size.

Promotion was initially rapid and based on ability and skill. As members of a volunteer auxiliary group, the WAACs got paid less than their equivalent male counterparts in the US Army and did not receive any benefits or privileges.

WAAC organizational insignia was a Rising Eagle (nicknamed the "Waddling Duck" or "Walking Buzzard" by WAACs). It was worn in gold metal as cap badges and uniform buttons. Enlisted and NCO personnel wore it as an embossed circular cap badge on their Hobby Hats, while officers wore a "free" version (open work without a backing) on their hats to distinguish them. Their auxiliary insignia was the dark blue letters "WAAC" on an Olive Drab rectangle worn on the upper sleeve (below the stripes for enlisted ranks). WAAC personnel were not allowed to wear the same rank insignia as Army personnel.

They were usually authorized to do so by post or unit commanders to help in indicating their seniority within the WAAC, although they had no authority over Army personnel. WAAC ranks (May, 1942 - April, 1943). WAAC ranks (April, 1943 - July, 1943). Assistant Director of the WAAC.

The organization was renamed the Women's Army Corps in July 1943[46] when it was authorized as a branch of the US Army rather than an auxiliary group. The US Army's "GI Eagle" now replaced the WAAC's Rising Eagle as the WAC's cap badge. The WAC received the same rank insignia and pay as men later that September and received the same pay allowances and deductions as men in late October. [47] They were also the first women officers in the army allowed to wear officer's insignia; the Army Nursing Corps didn't receive permission to do so until 1944. The WAC had its own branch insignia (the Bust of Pallas Athena), worn by "Branch Immaterial" personnel (those unassigned to a Branch of Service).US Army policy decreed that technical and professional WAC personnel should wear their assigned Branch of Service insignia to reduce confusion. During the existence of the WAC (1943 to 1978) women were prohibited from being assigned to the combat arms branches of the Army - such as the Infantry, Cavalry, Armor, Tank Destroyers, or Artillery and could not serve in a combat area.

However, they did serve as valuable staff in their headquarters and staff units stateside or in England. The army's technician grades were technical and professional specialists similar to the later specialist grade. Technicians had the same insignia as NCOs of the same grade but had a "T" insignia (for "technician") beneath the chevrons.They were considered the same grade for pay but were considered a half-step between the equivalent pay grade and the next lower regular pay grade in seniority, rather than sandwiched between the junior enlisted i. Private - private first class and the lowest NCO grade of rank viz.

Corporal, as the modern-day specialist (E-4) is today. Technician grades were usually mistaken for their superior NCO counterparts due to the similarity of their insignia, creating confusion. There were originally no warrant officers in the WAC in July, 1943. Warrant officer appointments for army servicewomen were authorized in January 1944. In March 1944 six WACs were made the first WAC Warrant Officers - as administrative specialists or band leaders. The number grew to 10 by June, 1944 and to 44 by June, 1945. By the time the war officially ended in September 1945, there were 42 WAC warrant officers still in Army service. There was only a trickle of appointments in the late 1940s after the war. Most WAC officers were company-grade officers (lieutenants and captains), as the WAC were deployed as separate or attached detachments and companies.The field grade officers (majors and lieutenant-colonels) were on the staff under the director of the WAC, its solitary colonel. [48] Officers were paid by pay band rather than by grade or rank and didn't receive a pay grade until 1955.

WAC ranks (September, 1943 - 1945). There were no chief warrant officer appointments in the WAC during the war because they did not meet the skill or seniority requirements for the rank. However, few servicemen did either.It required ten or more years of time in grade as either a warrant officer (junior grade) - a rank first created in 1941, staff warrant officer - a rank waitlisted since 1936, or an Army Mine Planter Service warrant officer - an Army sea auxiliary unit that was not allowed to recruit women. Brigadier General Mildred Inez Caroon Bailey. The Women's Army Corps Veterans' Association--Army Women's United (WACVA) was organized in August 1947. Women who have served honorably in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) or the Women's Army Corps (WAC) and those who have served or are serving honorably in the United States Army, the United States Army Reserve, or the Army National Guard of the United States, are eligible to be members.

The association is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization representing women who served their country in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Panama, Persian Gulf Bosnia and in Iraq and Afghanistan. WACVA sponsors an annual national convention and projects honoring women veterans. Local chapters of WACVA focus on volunteer work in Veterans Administration Hospitals and Community Service in the local and national community. The organization's newsletter THE CHANNEL keeps the members aware of our national business, projects and pertinent veterans information. First WAC Director Oveta Culp Hobby. Colonel Geraldine Pratt May b. [50] In March, 1943 May became one of the first female officers assigned to the Army Air Forces, serving as WAC Staff Director to the Air Transport Command. In 1948 she was promoted to Colonel (the first woman to hold that rank in the Air Force) and became Director of the WAF in the US Air Force, the first to hold the position. Charity Adams was the first commissioned African-American WAC and the second to be promoted to the rank of major. Promoted to major in 1945, she commanded the segregated all-female 6888th Central Postal Battalion in Birmingham, England. The 6888th landed with the follow-on troops during D-Day and were stationed in Rouen and then Paris during the invasion of France. It was the only African-American WAC unit to serve overseas during World War II. Due to her earlier experience serving with director Mary McLeod Bethune of the Bureau of Negro Affairs, she became Colonel Culp's aide on race relations in the WAC. After the war, she was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in 1948.Murray served at WAC headquarters during World War II. She became the first female judge in Rhode Island in 1956.

In 1977 she was the first woman to be elected as a justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island. She was the first woman to serve on a United States Army general court martial. In January, 1943, Captain Frances Keegan Marquis became the first to command a women's expeditionary force, [55] the 149th WAAC Post Headquarters Company.

[57] An Army history called this company one of the most highly qualified WAAC groups ever to reach the field. Hand-picked and all-volunteer, almost all members were linguists as well as qualified specialists, and almost all eligible for officer candidate school. Louisiana Register of State Lands Ellen Bryan Moore attained the rank of captain in the WACs and once recruited three hundred women at a single appeal to join the force. Captain Dovey Johnson Roundtree was among 39 African-American women recruited by Dr. Mary Bethune for the first WAACs officer training class.

Roundtree was responsible for recruiting African-American women. [60] After leaving the Army, she went to Howard University law school and became a prominent civil rights lawyer in Washington, D. She was also one of the first women ordained in the A.

In February, 1943 Lieutenant Anna Mac Clarke became, when a Third Officer, the first African-American to lead an all-white WAAC unit. Rutledge performed administrative work at the Army-Navy Staff College in Washington, DC. In March, 1944 WO(JG) Rutledge was one of the first six WACs to be granted a Warrant Officer's warrant. Chief Warrant Officer 4 Elizabeth C. Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jeanne Y.

Pace, was the longest-serving female in the army and the last active duty soldier who was a part of the WAC as of 2011. Her final assignment was Bandmaster of the 1st Cavalry Division where she retired after 41 years of service. [63] She is also a recipient of the Daughters of the American Revolution Margaret Cochran Corbin Award which was established to pay tribute to women in all branches of the military for their extraordinary service[64] with previous recipients including Major Tammy Duckworth, Major General Gale Pollock, and Lt General Patricia Horoho. Elizabeth "Tex" Williams was a military photographer. [65] She was one of the few women photographers that photographed all aspects of the military.

Mattie Pinnette served as personal secretary to President Dwight D. During the war years, popular comic strip Dick Tracy, drawn by Chester Gould, featured a young WAC spurning the romantic advances of a villain. Like wise Tracy's sweetheart Tess Truehart was a WAC Corporal who helped Tracy capture the German Spy Alfred "The Brow" Brau in 1943. A series of cartoon postcards distributed during the war years depicted WACS hitting Adolf Hitler over the head with a rolling pin We're Giving Him A Big WAC! ", standing in morning formation exercises "Don't Worry--Uncle Sam Is Keeping Us in Line!

", and window-shopping for civilian-style dresses "Just Looking... The 1945 film Keep Your Powder Dry features Lana Turner joining the WACs, which starred Agnes Moorehead, while sporting uniforms designed by Hollywood designer Irene and hair styled by Sydney Guilaroff. The 1949 film I Was a Male War Bride depicts Cary Grant as a French officer who married an American WAC, played by Ann Sheridan and their escapades as he attempts to emigrate to the United States under the auspices of the 1945 War Brides Act.

1952 film Never Wave at a WAC stars Rosalind Russell, who plays the daughter of a senator, and joins to be closer to her boyfriend in Paris, but her ex-husband causes problems, but she falls back in love with him. The 1954 film Francis Joins the WACS stars Francis the Talking Mule, who joins the Women's Army Corps. General Blankenship's secretary, Corporal Etta Candy (Beatrice Colen) in the first season of Wonder Woman was a WAC veteran. The song Surrender by Cheap Trick is about a babyboomer child of a former member of the WAC who served in the Philippines.Mare's War, a novel by Tanita S. Davis, centers around an African-American girl who joins the WAC. On an episode of The Looney Tunes Show, Granny tells Daffy Duck a story where she served as a WAC and prevented the theft of the Eiffel Tower and numerous artworks from The Louvre. Miss Grundy, a teacher in the Archie Comics series, was a WAC. The Phil Silvers Show makes numerous references to the WACs.

Several of the supporting cast, such as Sgt. Joan Hogan (Elisabeth Fraser), are members of the WAC and many of the gags and jokes in the show revolve around women in the army. First Officer Candidate Class, WAAC Officer Training School, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, 20 July - 29 August 1942; reveille. First Officer Candidate Class, WAAC Officer Training School, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, 20 July - 29 August 1942; close order drill.

First Officer Candidate Class, WAAC Officer Training School, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, 20 July - 29 August 1942; classroom instruction. First Officer Candidate Class, WAAC Officer Training School, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, 20 July - 29 August 1942; physical training. First Officer Candidate Class, WAAC Officer Training School, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, 20 July - 29 August 1942; chow line.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women's Army Corps. Women in the Air Force (WAF). Women in the United States Army. Women's Army Volunteer Corp.32nd and 33rd Post Headquarters Companies. Women were not subject to the military draft in World War II, but women as well as men volunteered to fight for their country.

Until 1948, three years after the end of the war, the armed forces were segregated (divided by race). White and black soldiers served in separate units. In 1942 the Army opened an officer training school for women at Fort Des Moines.

The camp on the south side of Des Moines had been the home of the first facility to train African-American male officers in World War I. The women who came to Fort Des Moines in 1942 were part of the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC, later shortened to WAC). At first only white women were accepted as candidates for WAC officer training. But because of political pressure, the camp was opened to black women as well. The army reserved 40 of the first 440 candidate positions for black women. At first white, Puerto Rican, Chinese, Japanese and Native-American women slept, ate and trained together while African-American women had separate facilities and training. This was at a time when much of the United States, especially the South, had laws requiring separate facilities for whites and blacks. The army insisted that WAC training should be the same for blacks and whites.Every effort will be made through intensive recruiting to obtain the class of colored women desired, in order that there many be no lowering of the standard in order to meet ratio requirements. At the request of the federal government a Des Moines attorney, Charles P. Howard, was directed to interview the black WAC candidates and find out if there was any evidence of discrimination on the Army post. He reported that none was related to him.

A reporter from a black newspaper in Pittsburgh traveled to Des Moines and wrote the same thing. Neither heard any evidence of jokes or insulting remarks or discrimination in training against black officer candidates. But black WACs were required to use separate dormitories, lunch rooms and swimming pools. And the women reported that when they left the training camp and went into Des Moines, they faced discrimination and sometimes hostile comments.

Black organizations like the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the YMCA protested the segregated facilities. In November 1942 the use of separate eating and sleeping arrangements ended. A black woman from Georgia, Sarah Murphy Palmore, graduated from the officer training program in 1942 with 35 other black women. She remembered that black families in Des Moines welcomed the black women at the camp and sometimes invited them home for dinner.Altogether 65,000 women of all races were trained at Fort Des Moines during World War II. They learned military sanitation, first aid, map reading and camp management.

Still, racial and gender stereotypes kept black women from many opportunities. A history of African-Americans in Iowa claims that World War II had a great impact on all women, black and white. Many of the obstacles and stereotypes confronting black WACs obstructed their white sisters as well.

The WAC was an overall success in coming to the aid of the nation in time of war in a conflict that demanded hard sacrifices from all Americans, male and female, black and white. In 1948 President Harry Truman ended segregation in the armed forces. He signed Executive Order 9981 that forbade the military from discrimination on the basis of race. AS WE OBSERVE Veterans Day tomorrow -- which this year honors in particular the American soldier of World War II -- we should find a moment to salute the 4,000 determined black women who fought almost unbelievable discrimination to serve their country in that conflict.With war erupting throughout Europe and Asia in 1941, Congress responded to the military's overwhelming personnel needs by allowing women to be incorporated into the armed services. By war's end more than 400,000 would serve in almost every capacity short of combat -- though in fact more than 200 were killed and many more were wounded and captured. Enthusiasm for the new women's units ran high among civil rights leaders and the black community, which saw an opportunity for black women to prove their worth as citizens and to challenge both official segregation in the military and widespread discrimination in American civilian life.

The Navy, Marines, Coast Guard and Army Nurse Corps announced they had no place for black women -- only whites need apply. The Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) alone was open to blacks, but even it limited their enlistments to the proportion of blacks in the civilian manpower force: 10 percent. Moreover, the WAAC would follow established Army policy; full integration was forbidden. The first group of 40 black women, selected by competitive examination from more than 4,000 applicants, entered the WAAC on July 20, 1942. They were formed into two companies, and officers were selected from among them. After basic training, some of the 40 attended the first officer candidate school for women at Ft. For the others, recruiters' promises of opportunities to learn new skills that might lead to good postwar jobs quickly proved empty.During the early days of the WAAC, blacks were too few to organize into separate companies, so whites and blacks lived and worked together. Even this limited integration produced immediate repercussions. As protests poured in from civilians, the War Department quickly ordered separate facilities for black Waacs and assured concerned congressmen that henceforth white and black women, even if they worked together, would not eat in the same mess halls or sleep in the same barracks. Although the War Department and the WAAC continued to stress advancement for qualified black women on an equal basis with whites, segregationist practices were the reality.

Black women were not assigned where they were not wanted, and most commanders refused to accept them. Black WAAC officers could only command black units. And under no circumstances could black officers supervise white officers junior to them in grade. The War Department stood adamant against desegregation, proclaiming a public policy of segregation without discrimination.

Some WAAC training centers and many Army bases were located in the South, where public bus and rail transportation was totally segregated. Black military women traveling between North and South were not allowed to enter into dining cars of trains until all whites had eaten. They then ate with a curtain drawn around them.

No menu was offered nor prices quoted. One black second lieutenant who refused to move from her seat on a bus in Montgomery was beaten, dragged off the vehicle, arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced to 30 days in jail. Many years later a black woman named Rosa Parks on another Montgomery bus set off a nationwide social revolution.

Besieged by complaints and increasingly under fire from black activist groups and organizations, the War Department asked the U. That office replied that the Supreme Court had found segregation on public transportation to be legal and that Army members must comply with regulations imposed by carriers. Local commanders rarely did anything to interfere with the prevailing Jim Crow laws. Discrimination against black Waacs was bound to cause an explosion, and not necessarily in the South.In November 1944, a company of 60 black medical technicians in the now renamed Women's Army Corps (WAC) arrived at Lovell General hospital at Fort Devens, Mass. Although military hospitals were overcrowded and understaffed, black women were not allowed anything but the most menial tasks.

Instead of being assigned to their military specialties, the 60 new arrivals were put to work washing windows and scrubbing floors. White civilians were quickly schooled in such routine procedures as temperature-taking, catheterization and physical conditioning, tasks which the black Wacs were already trained to do. The women complained but were ignored. On March 7, 1945 all 60 began a sit-down strike and requested an interview with the hospital commander. At first he refused to meet, but finally did so and delivered a tongue-lashing. "Black girls, " he told the Wacs, are "fit only to do the dirtiest type of work" because that's what Negro women are used to doing. " He would not have black Wacs serving as medical technicians -- "They are here to mop walls, scrub floors and do all the dirty work -- and he hoped that the war lasted 25 more years. The women walked out on him. On March 10, the 60 were officially commanded to return to work or be held in violation of the Articles of War for failing to obey a lawful order in wartime. Of the 60 strikers, four refused to return to duty and were arrested. The court martial brought out numerous instances of discrimination and inferior working conditions, and the four were repeatedly told that since they were black they were not to perform as medical technicians. The women were found guilty and could have been sentenced to death. But the court was lenient: It sentenced the women to a forfeiture of all pay and allowances, one year at hard labor and then a dishonorable discharge. Black organizations, press, communities and congressmen now reacted. They found it unbelievable that with a nursing shortage in the midst of a world war, a hospital commander would hamper efforts by black Wacs to help nurse wounded soldiers -- and that they would get a year at hard labor for trying.The uproar, the allegations at the trial and complaints to the White House ensured the War Department's prompt response. The convictions were reversed and the charges dismissed. Blacks wanted the Lovell commander investigated and punished, but the War Department closed the matter. Despite black sacrifices and contributions, the Army held fast to its policy of segregation until long after the war against the "master races" in Germany and Japan had ended. RitaVictoria Gomez, a history professor at Anne Arundel Community College, is an Air Force reserve major and is writing the official history of women in the Air Force.

Anyone who has served overseas away from family and friends knows the power of a letter from home. Troops, Red Cross and uniformed civilian specialists serving in Europe. Women's Army Corps 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion standing at attention prior to their deployment to Europe during World War II. Women's Army Corps Maj. Charity Adams (forefront), 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion commander, and Army Capt.

Abbie Noel Campbell, 6888th executive officer, inspect the first soldiers from the unit to arrive in England on Feb. In February 1945, the "Six-Triple Eight, " as it was known, went to England becoming the first and only all-black WAC unit to be sent overseas during WWII."They had asked if we could get it done in about six months, " King told CBS News in November. We were able to get it done in three months. Edna Cummings hopes to see the 6888th recognized with a Congressional Gold Medal. "During a time when they were denied basic liberties as Americans, they still wanted to serve the United States, " Cummings told CBS News. As such, the identical bills S.

3138 - "Six Triple Eight" Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2019 - have been introduced in the Senate and House, respectively. 30, 2018, a monument to these women was dedicated at the Buffalo Soldier Commemorative Area on Fort Leavenworth, Kan. Furthermore, on March 15, 2016, the U.

Army Women's Foundation inducted the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion into the Army Women's Hall of Fame. That's a morale booster. That made me feel good that I had done my part.